Jerry JonesBritain desperately needs to revive its manufacturing industry. Compared with other advanced economies, Britain’s economy is overdependent on the financial sector. For example, bank holdings in Britain amount to over 300 per cent of GDP, which is double that in the Euro area, and four times that in the US. And, since the current crisis largely originated in the financial sector, Britain’s economy is likely to be hardest hit. Indeed, debt write-downs by banks based in Britain during the coming period, according to IMF estimates, will amount to some 25 per cent of GDP. This compares with only 6 per cent in the Euro area, and 7 per cent in the US. Britain, of course, invented manufacturing industry. But ever since bankers and others in finance, in the late nineteenth century, discovered that they could make more money overseas than investing in Britain, manufacturing has tended to be neglected. Other countries are not forever going to allow financial institutions based in the City of London, acting as an offshore tax haven, to benefit at their expense. Britain needs to diversify.

The Government had the chance to kick-start the revival of manufacturing when it was forced to rescue three of Britain’s high street banks facing bankruptcy. The banks could have been taken wholly into public ownership and used as a conduit for channelling the funds created by the Bank of England in its so-called ‘quantitative easing’ programme to invest in manufacturing. That is what the authorities did in China through its state-owned banks, and its economy has carried on growing. In Britain, in contrast, the funds created have been stuck in banks, used mainly to strengthen their balance sheets, instead of being invested in the real economy, which is what is needed to overcome the crisis.

Some immediate investment prioritiesFor a start, the funds could have been invested in a major house-building programme. This would have killed several birds with one stone. First, this would have helped overcome the chronic shortage of affordable homes, without which, with numbers seeking homes on the increase in the coming period, the situation will go from bad to worse. Second, it would have provided jobs for the thousands of unemployed construction workers. This, in turn, would have created economic demand for goods and services on which the newly employed builders would seek to spend their wages, stimulating investment and employment in their production and supply. Furthermore, investment in construction would have stimulated investment and employment in the manufacture of the various inputs required by the revitalised construction industry. In addition, the new employment and spending created would have boosted tax revenues, thus enabling the government to recoup much of the money spent.

Another use of the funds could have been to extend investment in infrastructure, especially the railways, which are desperately backward compared with most other advanced countries. This would have had similar knock-on effects. Moreover, investment in infrastructure (and also to some extent in construction) feeds directly into land values, which could be recouped through a land value tax that would make the investment self-funding.

Another important area for public investment is in the development of renewable energy technologies, much needed if Britain is to achieve its targets of reducing carbon dioxide emissions. Some experts have estimated that as much as 80 per cent of Britain’s energy needs could come from a vast network of offshore wind farms. This would obviate the need for nuclear power stations, with all the hazards involved – which, in any case, if one takes account of the whole process from mining to the production of the nuclear fuel and dealing with the radioactive waste, emit as much carbon dioxide as conventional power stations. (Ministers try to cover themselves here by inserting the phrase ‘at the point of generation’ when referring to the supposed benefits of nuclear power).

There are many other areas of manufacturing that the government could foster to create jobs and skills, and to promote faster economic growth with minimal environmental impact. But for this, a coherent strategy is needed.

The need for a new international trade policyFirst, it needs to be pointed out that if the Government were to pour funds into construction and manufacturing, this could simply benefit other countries at our expense by drawing in imports. If the economy is to expand, Britain will need to import, but it needs to be ensured that what is imported has the greatest economic impact. In other words, there will need to be import controls. This, of course, will immediately bring howls of ‘protectionism’, so indoctrinated are most people, including many on the Left, that trade must be ‘free’ at all costs – which, in practice, benefits the giant transnational corporations at the expense of everyone else. In fact, selecting what to import and how much – which should be the democratic right of all countries – creates the opportunity for economies to develop much faster than otherwise, which would benefit international trade far more than so-called ‘free trade’. That is because the faster an economy grows, the more it will need to import (since no country can be self-sufficient), and therefore, the more it will have to export.

Again, China is a good example. Because its economy has been growing so fast – ‘in spite of’ selecting what it imports – it is enhancing international trade because of its need for raw materials and high technology capital goods. This, of course, benefits the countries exporting those commodities.

People often hark back to the 1930s, when it is said that ‘protectionism’ caused the worldwide depression. In fact, the cause of the depression was not ‘protectionism’ as such, but mistaken economic policies (not much different from now) that failed to promote economic growth. Indeed, the main country that carried on providing an extensive market for exports from other countries at that time was also the country that most controlled its imports – namely the USSR, whose economy was expanding rapidly due to its huge industrialisation programme, which is analogous to the position of China today.

To be sure, it would be better if trade policy was decided at international level through the World Trade Organisation. But for this to happen, its members would have to abandon their ‘free trade’ dogma, and recognise the fact that all countries, in order to optimise economic growth, need to control what they import to a greater or lesser extent – the more so, the less developed are their economies. A system I have proposed is to allow every country an average tariff or equivalent in inverse proportion to its GDP per capita, leaving it up to each country to decide how the tariffs are distributed. Thus, less developed countries would have the higher levels of protection that they need. They would be able to impose relatively high tariffs on luxury imports and products being produced locally for the first time, offset by very low tariffs, or perhaps subsidies, on imported technologies that they need for developing their economies. More developed countries, on the other hand, could use their much lower ‘allowances’ to limit imports of products tending to undermine employment in certain sectors, giving enterprises the chance to adjust, cut costs, or diversify.

Meanwhile, schemes based on those principles could be negotiated on a bilateral basis. Already, many bilateral trade deals have been agreed, but they need to be made more equitable. At present, many tend to favour the more developed countries, especially the EU and the US, at the expense of less developed countries – which reflects the weaker bargaining positions of less developed countries – so that trade does not grow and benefit the countries concerned as much as it could have done.

The need to raise wagesOnce imports are properly planned through selective controls, it becomes possible to introduce many other measures that would benefit manufacturing, and the economy as a whole.

For example, it would be possible to raise substantially the minimum wage – with knock-on effects on wages for more skilled workers – without this having the effect of drawing in more imports at the expense of domestic producers. This would have the effect of boosting economic demand for goods and services, and therefore stimulate investment in their production and supply. Raising wages would, of course, increase costs for employers, but businesses would benefit from the bigger domestic market for their products.

This measure could be backed up by a new Bill of Rights for employees (including repealing the current laws that restrict trade union activities introduced by the Tories in the 1980s, which New Labour had promised but reneged on). This would improve the bargaining positions of workers and their trade unions, and therefore terms and conditions of employment.

Measures to deal with insolvencyNext, new measures could be introduced to deal with the problem of insolvency, through the establishment of an insolvency agency at central and local governmental levels. They could establish a revolving fund, whose function would be to advance low cost loans to help rehabilitate failed businesses – perhaps in a new productive activity – aimed at maintaining employment and workers’ skills. In many cases, the best option might be to convert the businesses into worker-owned co-operatives. This would have the advantage that the businesses would only have to cover workers’ wages and the costs of inputs, maintenance and marketing, and would not have to generate the high returns demanded by outside shareholders or private capitalists.

Furthermore, new laws could be introduced to require companies to make their accounts more transparent and available to workers and their advisors, giving workers powers to prevent asset stripping, and companies being deliberately run down, thus making insolvency less likely. This would be helped further if the auditing of company accounts became the responsibility of a public agency – perhaps a much expanded National Audit Office (which currently is only responsible for the accounts of central government departments and agencies). This would replace the private accountancy firms that are currently responsible, thus eliminating the conflicts of interest arising from their other role as consultants (a major activity of which is to manipulate company accounts to avoid tax).

Capital controls - and the need to abolish offshore tax havens

Another important measure needed to ensure that the savings and investment resources generated by workers are used for the benefit of Britain’s economy would be to re-introduce capital controls. For these to be effective, all dealings with businesses and subsidiaries based in offshore tax havens would have to be made illegal (preferably through international agreement, with suitable compensation for small island tax havens). It was precisely the mushrooming of offshore finance that did most to undermine the capital controls that were in place more or less everywhere in the 1950s and 1960s. Instead of reining in these activities, governments caved in to the lobbying of the big banks. They allowed these offshore havens to flourish, and eventually deregulated international capital flows almost entirely. As is now evident, this not only greatly benefited the rich at the expense of the poor, thus exacerbating inequalities worldwide (countries and people), but also is what made the current economic crisis far deeper and more destructive than it might have been.

The role of a revamped Department of Trade and Industry

If a government is serious about enhancing the role of manufacturing in a more diversified and re-balanced economy, and optimise economic growth, it will need to re-introduce some form of economic planning. This could be achieved through a re-established and revamped Department of Trade and Industry. Among its tasks would be to:

• Manage trade policy to maximise the benefits of international trade for Britain’s economy;

• Co-ordinate investment in the various sectors of manufacturing, including in the public sector where appropriate;

• Administer taxes and subsidies to favour industries having the greatest impact on economic development and those needed to reduce emissions and other adverse environmental effects;

• Oversee and help fund research and development endeavours carried out by companies, research institutions and universities;

• Introduce a new system of training through the establishment of manufacturers’ associations in the different sectors, linked to technical colleges and universities, thus giving workers the theory and skills needed to maximise their contribution to economic development.

Conclusion

Once one abandons the dogmas of privatisation and ‘hands-off’ government, all of the measures proposed above to revive manufacturing industries, and reduce their environmental impact, are perfectly straightforward and obvious. Why cannot governments see this? Why cannot they see that ‘hands off’ allows the rich and powerful, the giant transnational corporations and financial institutions, to dictate policies – which, as is now evident, has led to the growing divide between rich and poor, and now, probably, one of the worst economic crises since the start of the industrial revolution, the brunt of which they expect ordinary people to bear. It is surely time to change course. Britain, following in the footsteps of China, could show the way.

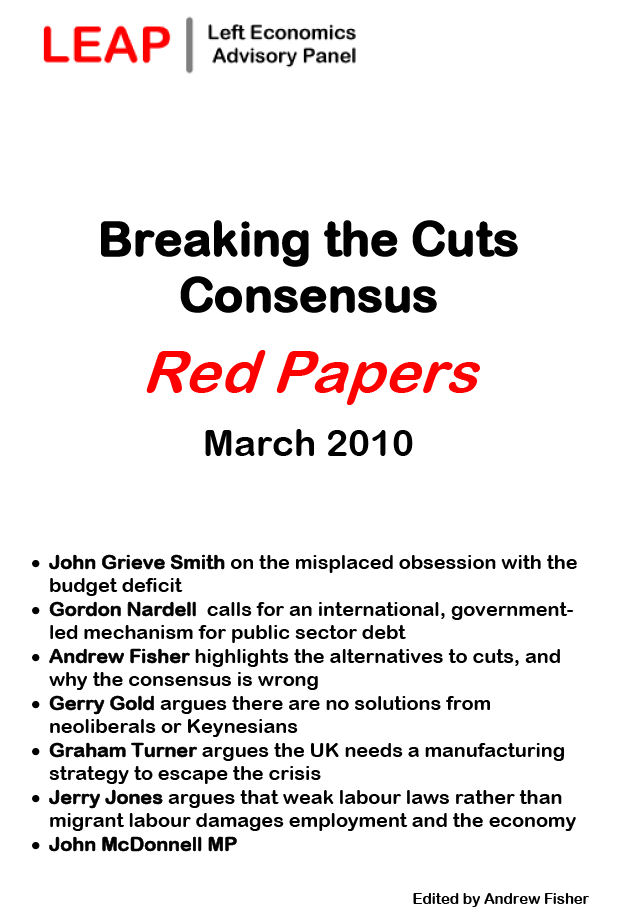

*This article is taken from the LEAP Red Papers: The Cuts, which can be discussed in full on the LRC website