Today's shareholders are often foreign, functioning more like traders than owners – why would social justice bother them?

Prem Sikka

The deputy prime minister, Nick Clegg, and the business secretary, Vince Cable, are on a charm offensive. People facing wage freezes are being told that the government will crack down on runaway executive remuneration. A key mechanism is to encourage shareholders to take a more active role, whatever that might mean, because in the words of Clegg, "they own the companies, after all". The evidence shows that such claims are flawed.

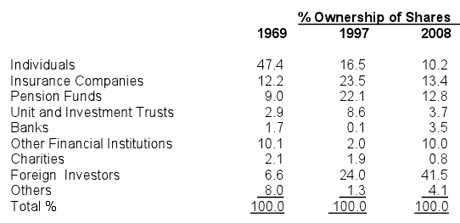

In the last 30 years there have been massive changes in shareholding patterns. Shareholders are now traders in shares rather than owners. They have little long-term interest in a company and little inclination to invigilate them in the public interest. The table below is compiled from various surveys published by the Office for National Statistics and shows the pattern of share ownership in UK-listed companies:

Despite the giveaway of shares in privatisations and tax incentives to buy shares, for example through ISAs, direct share ownership by individuals has declined dramatically. The foreign ownership of UK companies has increased and 41.6% is held abroad by oligarchs, sheikhs, sovereign funds and foreign entities. A major change not captured by the above data is that the average duration of share holdings has fallen from around five years in the mid-1960s to around two years in the 1980s, and by the end of 2007 it declined to around 7.5 months. I know of financial institutions who now churn their portfolio every three months to pick winners, and that trend is already consolidated in banks. In October 2011, Andrew Haldane, a member of the Bank of England financial policy committee noted that "average shareholding periods for US and UK banks fell from around three years in 1998 to around three months by 2008. Banking became, quite literally, quarterly capitalism".

So the government is planning to tackle fat-cat pay by empowering shareholders. That did not happen even when a vast majority of the shares were held in the UK and for a longer duration. It certainly is not going to happen when shareholders have a short-term interest and primarily function as traders and speculators, rather than as owners. It is difficult to see why oligarchs, sheikhs and other foreign owners would be bothered by high levels of executive remuneration as their main concern is the returns on their investment rather than any sense of social justice in the UK. Individuals may have indirect ownership through insurance companies and pension funds, but they do not elect directors and cannot mandate these entities to vote in any particular way. In any case, directors of these entities have incentives to maintain high executive remuneration because it provides the benchmark for their own rewards.

Even if some shareholders could muster a resolution at the annual general meeting (AGM) to oppose fat cat pay, their chances of success are slim: directors are permitted to cast thousands of votes to defeat any unwelcome resolution. Even if a resolution is passed it is only advisory rather than binding on directors. In Clegg's world, shareholders are not only the owners but also the main risk-bearers. This is not quite so either: the banking crash has vividly demonstrated that risks are borne by savers and taxpayers. Shareholders have the benefit of limited liability but taxpayers have virtually written a blank cheque. At many other entities, shareholders only provide a minority of the finance capital and thus do not bear all the risks. In any case, their liability is limited. Employees also bear a heavy cost because their jobs and pensions depend on corporate wellbeing.

To curb fat-cat pay, the government needs to empower those with the long-term interests in a company. This requires not only putting employee representatives on remuneration committees, as Clegg is hinting, but putting them on company boards and changing the way the UK companies are governed. The debate about democratisation of major corporations is long overdue.

*This article first appeared at Guardian Comment is Free

No comments:

Post a Comment